The State of the World’s Children 2016

The lives and futures of millions of children are in jeopardy. We have a choice: Invest in the most excluded children now or risk a more divided and unfair world.

Introduction

A fair chance

Every child has the right to a fair chance in life. But around the world, millions of children are trapped in an intergenerational cycle of disadvantage that endangers their futures – and the future of their societies.

Hafsa Khatun, 4, hides under the table to avoid eating her greens. (Khulna, Bangladesh)

It’s a typical Friday afternoon in the city. Amena has prepared an elaborate family meal of dal, rice, stewed greens, pumpkin, chicken curry and fish – her daughter Hafsa’s favourite. Hafsa doesn’t feel like sitting around with the adults, though; she’d rather go outside and play. So she makes a game of it, hiding under the table to avoid eating her greens. Eventually, Amena gives up; but she makes sure Hafsa drinks all her milk before she is allowed to dash off with the neighborhood kids.

The family of five doesn’t have much. At US$64 a month, rent for their modest two-bedroom flat in the city eats up about a third of the combined income that Hafsa’s father and grandfather bring in. But it’s enough to provide Hafsa with a loving, nurturing environment. The bedroom shared by Amena and her husband doubles as a playroom: Rainbow-coloured tinsel dangles from the ceiling, and a stack of stuffed animals sits neatly in the corner. Amena, who only finished the eighth grade, is trying hard to make sure her daughter grows up in a stimulating environment. Every night before bed, they recite the alphabet in Bangla and English, so that Hafsa can start school on a strong footing.

There is nothing unique or unusual about Hafsa’s situation. She is simply enjoying the basic rights that every child is entitled to: safety, health, play and education.

Around the world, millions of children are denied these rights and deprived of what they need to grow up healthy and strong – because of their place of birth; because of their race, ethnicity or gender; or because they have a disability or live in poverty.

Rexona Begum shares a lunch of rice and potatoes with her daughters, Moriom, 6, and Sumiya, 5, in Satkhira, Bangladesh.

A vicious cycle of disadvantage

In the countryside, Rexona Begum sits down for a lunch of rice and curry potatoes with her daughters Moriom, 6, and Sumiya, 5.

Unlike Amena, Rexona doesn’t have to coax her children to eat. They clear their plates, and when the meal is finished, Moriom dutifully heads over to the moss-covered pond adjacent to their mud home to wash her dish.

Recently, the local clinic diagnosed Sumiya with malnutrition. Rexona didn’t need a doctor to tell her that her daughters aren’t doing well. She can see it in their small frames and their lack of vitality. They don’t look like her neighbours’ children, who, she says, are “healthy and robust”.

Part of the problem is that the family doesn’t have easy access to clean water. The nearest tap is a kilometre away, and until recently it provided only unfiltered water. As a result, Moriom and Sumiya have suffered multiple bouts of diarrhoea, which have compounded the effects of their malnutrition. If Sumiya does not get better, she could become stunted, with long-term, irreversible effects on her physical and cognitive development.

Upon advice from the clinic, Rexona has started to incorporate more vegetables into her cooking, often salvaging the leafy greens her neighbours discard. She has also invested in five chicks, so that her girls can have eggs. But she simply doesn’t have the resources to follow many of the clinic’s nutrition recommendations.

Rexona does her best to provide for her children. When she is not at home caring for them, she works in other people’s houses, mopping the floors or spreading fresh mud on the exterior walls. Still, many basic necessities are beyond her reach. Even with the income her husband and her son bring in as day labourers, she cannot afford to purchase essentials, like meat, fish or eggs.

The poverty that now hampers Rexona’s ability to feed her daughters adequately has been limiting the choices available to her ever since she was a child. Rexona grew up in a poor family and was only able to attend school until Grade 4. Her husband, from an even poorer family, never went to school. He has been working since he was a young boy to help support his family. For all she and her family lack, Rexona says times are better than when she was growing up. “Our life was more difficult. We didn’t have as many opportunities.”

Rexona has modest dreams for her children. “I want my kids to be educated and to be good human beings”, she says. “I’ll help them finish school, if I can.” But she doubts that she and her husband will be able to provide them this basic right. Her 15-year-old son is already a full-time labourer.

Even with three incomes, Rexona and her husband struggle to give their children the basics – a healthy start, strong nutrition and an education. But if her family doesn’t get additional support, her daughters are likely to inherit the deprivations she and her husband grew up with – and in turn pass them on to their own children.

They will become part of a vicious, intergenerational cycle that curtails children’s opportunities, deepens inequality and threatens societies everywhere.

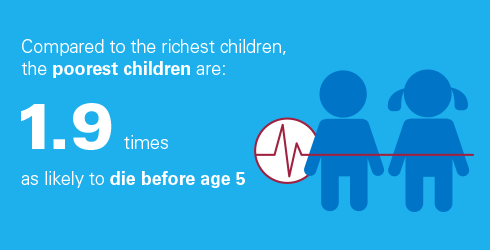

Trapped in a cycle of disadvantage, children from the poorest households, like Sumiya, are effectively pre-selected for heightened risks of disease, hunger, illiteracy and poverty based on factors entirely outside their control. They are nearly two times as likely to die before the age of 5, and in many cases, more than twice as likely to be stunted as children from the richest households. They are also far less likely to complete school, meaning that those who survive this precarious start find little opportunity to break free from their parents’ poverty and to shape their own futures.

A UNICEF funded pre-primary school caters to the poorest residents of Satkhira Sadar, Bangladesh. Early childhood interventions can give children born into poor and non-literate homes a boost, so they have a better chance of success when they start school.

Choosing to break the cycle

This vicious cycle is not inevitable. We can choose to change it. There are proven strategies for reaching the hardest to reach and expanding opportunity. When governments adopt policies, programmes and public spending priorities that target the most deprived children, they can help transform those children’s lives and their societies. But when they fail to focus on meeting the needs of the most marginalized, they risk entrenching inequities for generations to come.

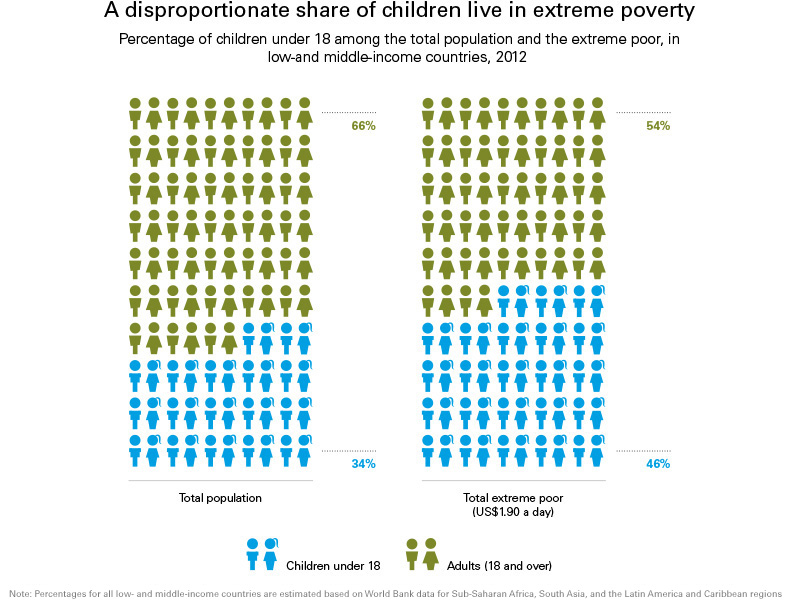

Around the world, children make up nearly half of the almost 900 million people living on less than US$1.90 a day. Their families struggle to afford the basic health care and nutrition needed to provide them a strong start. These deprivations leave a lasting imprint; in 2014, nearly 160 million children were stunted.

Despite great progress in school enrolment in many parts of the world, the number of children aged 6 to 11 who are out of school has increased since 2011. About 124 million children and adolescents do not attend school, and 2 out of 5 leave primary school without learning how to read, write or do basic arithmetic, according to 2013 data. This challenge is compounded by the increasingly protracted nature of armed conflict. Nearly 250 million children live in countries and areas affected by armed conflict, and millions more bear the brunt of climate-related disasters and chronic crises.

It doesn’t need to be this way.

By shifting priorities and concentrating greater effort and investment on children who face the greatest challenges, governments and development partners can make sure every child, including those born into poverty like Sumiya, has a fair chance to achieve her full potential – and realize a future of her own making.

Chapter 1:

A chance to survive

The world has made tremendous progress in reducing child mortality. But unless we change course, by 2030, 69 million children will die before reaching their fifth birthdays – most of them from poor countries.

Kaltum Mallamgrema, 40, at her home in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Three weeks ago, Kaltum lost her eighth child to stillbirth.

When the labour pains came, Kaltum handled the delivery like she had all seven of her previous births: at home, alone.

There was no mad rush to the hospital; no experienced staff standing by, ready to spring into action in the event of a complication; no skilled birth attendant to count the frequency of her contractions or measure the dilation of her cervix. Just an abundance of blood, nausea and the bare concrete walls of her temporary home.

By the time the baby arrived, she was already gone. Kaltum never had a chance to give her daughter a name or cradle her in her arms. She was never able to ask a doctor what went wrong. “It is God’s will”, is all she knows for sure. “We must be patient.” For around 1 million babies born in 2015, their first day of life was also their last.

Many of these babies were born with the odds stacked against them. Children’s deeply unequal chances of surviving their infancy and early childhood depend on a range of factors, including the wealth of their families, whether they’re born in a city or in the countryside, whether they’re born into a majority ethnic or religious group in their society – and whether the country they’re born in is rich or poor.

Despite global progress in reducing deaths of children under 5 since 1990, children born in sub-Saharan Africa, where Kaltum lives, are still 12 times more likely than those in high-income countries to die before their fifth birthday.

The overwhelming majority of these deaths could be prevented through well known, low-cost and easily deliverable interventions. Regular check-ups make it possible to spot complications early, and address them before they end a child’s – or mother’s – life. Micronutrient supplements help pregnant women stay healthy and give their babies the nutrients they need to develop. Skilled birth attendants and the essential care they provide to mothers and newborns can also dramatically improve prospects for safe delivery and children’s survival in the fragile first month of life when 45 per cent of under-5 deaths occur. But access to these basic services is marked by extreme inequity – and this is one of the main reasons behind the staggering disparities in children’s chances of surviving their early years.

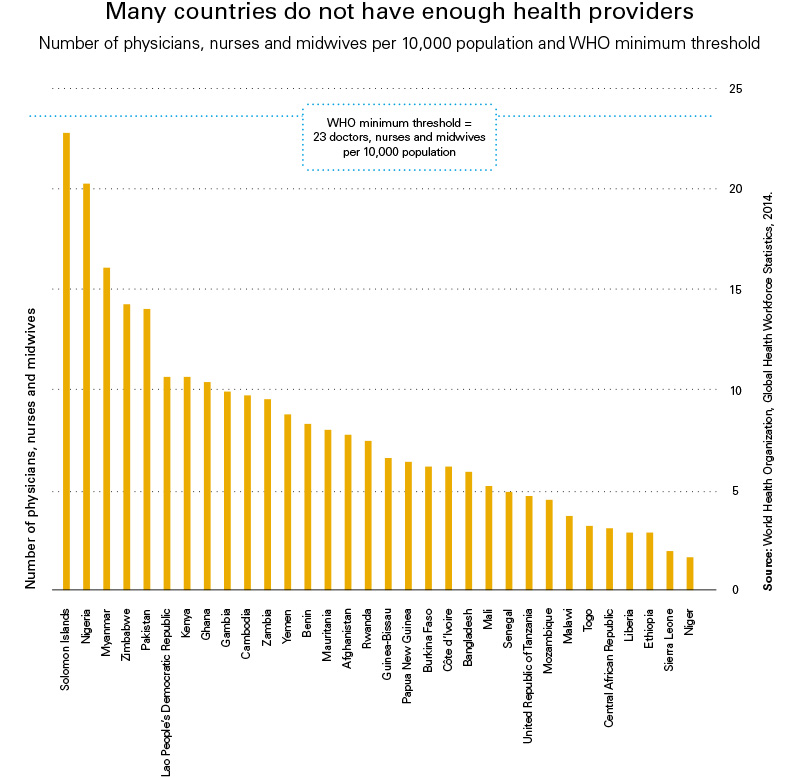

Often, there are simply not enough health providers to reach all mothers and children with these critical services. According to an estimate from the World Health Organization, covering basic health needs takes at least 23 health workers for every 10,000 people. Countries falling below this threshold struggle to provide skilled care at birth as well as the emergency and specialized services that some babies require.

Sub-Saharan Africa has 1.8 million fewer health workers than its population needs – a staggering deficit. One of the consequences is that women in the region face a 1 in 36 chance of dying from pregnancy-related complications over the course of their lives, compared to 1 in 3,300 in high-income countries. Without concerted action to recruit more skilled health workers and connect them with the people who need care the most, the deficit will rise to 4.3 million over the next 20 years as the population grows – a terrifying prospect for millions of women like Kaltum, and for their families and communities.

Vast disparities in child survival

Remi and Temitoye Falayi dote over their three-month-old daughter, Oluwatomini. Despite a complicated pregnancy, Oluwatomini arrived healthy and on time via a scheduled caesarean section at a well-equipped hospital in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja.

Across the world, women from the poorest 20 per cent of households are less than half as likely as those from the richest 20 per cent to have a skilled attendant at birth. Kaltum is among that poorest 20 per cent. Her neighbourhood in north-eastern Nigeria has a primary care clinic, but she didn’t go because she has no money to pay for its services.

Children from Nigeria’s poorest families, like Kaltum’s, are more than twice as likely to die before age 5 as those from the richest.

Behind regional data lie vast disparities within countries. Even in richer countries, the health and survival prospects of the poorest, most disadvantaged citizens can lag significantly behind the average. In the United States of America, for instance, data from 2013 show that infants born to African American parents were more than twice as likely to die as those born to white parents.

In Europe, children and families from the Roma community have a harder time getting the health services they need compared to those from ethnic majority populations. As of 2012, only 4 per cent of Roma children in Bosnia and Herzegovina had all the recommended vaccinations, compared to 68 per cent among non-Roma children. The effects of this neglect can be seen in children’s health and wellbeing: For example, one in five Roma children in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia are moderately or severely stunted.

Child survival begins with women’s health

It’s a celebratory time in the Dervišaj household. Ermina and Durmiš have just welcomed a new daughter to the family. In her honour, their relatives bought the couple a new stove to help keep their room warm through the cold Serbian winters.

But their happiness is tinged with worry. It has been a month since baby Kaja was born, and Ermina still hasn’t brought her home from the hospital. She vis

Ermina Dervišaj with her husband, Durmiš, and their six-year-old son, David, at their home in Kotež, a suburb of Belgrade, Serbia. One month ago, Ermina gave birth to a premature baby.

Social services consider babies like Kaja to be at risk of abandonment. She was born two months premature, and her parents have limited means to support even a healthy child, let alone one with special needs. Kaja’s situation might have been different had Ermina had access to the health care she needed when she was pregnant. Since her previous pregnancy ended in stillbirth, Ermina was prescribed medicine for maintaining pregnancy. But she could not afford to take it regularly. “When I had the money, I bought the medicine. But when we didn’t have any, I had to wait.”

Ermina requested support from the Centre for Social Welfare, but she was turned down. “I wanted to be enrolled on a list for the soup kitchen, but we were told that we are fit for work and are ineligible.” Like many of Serbia’s Roma people, Ermina’s husband Durmiš works in the informal economy, finding irregular work as a garbage collector. Ermina looks after her son, who is not yet in school. Even if she wanted to work outside the home, her employment prospects are dim. The official unemployment rate in Serbia is 18.5 per cent, and Ermina doesn’t have a primary education.

Ermina and her husband work hard to provide for their children. The two-story home they share with Durmiš’s family in a quaint suburb of Belgrade is the fruit of nine years of steadfast saving. The entire family have pooled their resources, building piece by piece as the money comes in. So far they have managed to complete just two rooms, but they can’t afford the 1,000 euros it costs to connect to the electrical grid.

The young couple could not survive without their extended family’s support. Still, without greater help from the community, Ermina and her husband will continue to struggle to provide a better future for David and Kaja. Because they are Roma, their children’s chances of something as basic as survival lag behind the national average.

Thanks to concerted efforts by the government, international agencies and NGOs, this outlook has been gradually improving, but there is still a long way to go. Ermina can attest to that. She herself grew up during a period of civil war. Today, Serbia is at peace – but, she says, “I wouldn’t say [my children] have better opportunities now.”

Community health workers make a difference

In a trailer park on the outskirts of Belgrade, Sonja Selimović is feeling more optimistic. Her settlement has running water, toilets and electricity. She has been living there for six years, ever since the government dismantled her former neighbourhood in town – a “cardboard city”, as she describes it, with no electricity or water.

Sonja says her life has been transformed thanks to the help of Vesna Jovanović, a Roma health mediator who visits the settlement every other day. “Vesna helped us enormously. Not only me, she helped all of us.”

Sonja Selimović with her children, Andela and Alen, outside their home in Palilula, Serbia. Sonja has received medical support from a Roma health mediator.

Vesna works to connect Roma families with health and social services. Scattered throughout Serbia, the 75 mediators are Roma themselves, so they speak Romanës and understand the community’s concerns – including their misgivings about the state and those who work for it. Vesna explains that, as an employee of the state, she had trouble gaining the community’s trust when she first started the job five years ago. “They were very sceptical at the beginning. They kicked me out. They didn’t even want to talk to me.”

Gradually, she managed to prove her worth. By coordinating with the primacy health care centre, Vesna brought nurses, paediatricians and gynaecologists along on her visits. Today, many of the settlement’s residents rely on Vesna to help them navigate the complex web of health and social services that they often encounter as hostile and discriminatory.

“Vesna is like a mother or a sister to us. We can call her in the middle of the night and she comes without any problems”, says Sonja. Vesna helps the community file the paperwork they need to access services, makes phone calls on their behalf and sometimes even accompanies them to health facilities. When Sonja is unsure of the doctor’s instructions, she turns to Vesna. “She always explains to me what the doctor didn’t have time to explain.”

Before she met Vesna, Sonja, now a mother of two, spent 13 years trying to get pregnant. Sonja believes that Vesna’s help connecting her with a qualified doctor is what made the difference. “If it hadn’t been for Vesna, I’m not sure I would have had this baby.”

Community health workers like Vesna make a real difference. In communities that have a hard time getting the services they need – like Europe’s Roma communities – as well as in many low- and middle-income countries that struggle to build strong health systems that can cover remote, poor and disadvantaged populations, community-based health interventions have been a key driver of progress in child survival.

Community health workers expand the reach of care, linking vulnerable people to high-impact, low-cost interventions for maternal, newborn and child health. But increasing the number of these critical health workers so they can reach the communities in greatest need will take deliberate choices to direct policies, public spending and health programming to meet the needs of the most disadvantaged children.

Chapter 2:

A chance to learn

Progress in expanding access to education has stalled. Unless we act now, by 2030, more than 60 million primary school-aged children will still be out of school – more than half of them in sub-Saharan Africa.

Muhammad Modu, 15, supports himself by collecting garbage in Maiduguri, Nigeria.

In a gated compound just off the main road that runs through the Mairi Garage Market in Maiduguri, Nigeria, 15-year-old Muhammad Modu is hard at work.

Wielding a twig barely a foot long, Muhammad sifts through the smouldering refuse of his middle class surroundings. With the sun pounding down on him and the smoke eating at his plastic flip-flops, his body feels like it’s on fire. But the hardest part, he says, is waiting for the trash to arrive. You never know if you’ll find much to make the wait worthwhile. After two to three days of this painstaking work, Muhammad gathers enough material to sell for N150–200, or US$0.75–$1.00.

Amidst the prizes – plastic bottles and scrap metal – he occasionally uncovers items that captivate him, even if he can’t sell them. His favourite finds are books. “I’m always impressed with photos of children in school or playing football”, he explains.

Muhammad used to be one of those children. That was until two years ago, when Boko Haram sacked his village and sent his family fleeing through the bush.

Today, Muhammad is one of the approximately 124 million out-of-school children and adolescents throughout the world.

He is also one of an estimated 75 million children whose education has been disrupted by crisis. Complex emergencies and protracted crises – sparked by violent conflict; natural disasters, including those linked to climate change; or epidemics – do not just temporarily interrupt children’s lives and schooling. They can close the doors on education for a lifetime.

“I used to dream that I could be a soldier, or something like that. But now I’m not in school, so I don’t know what I could be in the future.” – Muhammad Modu, 15

Moving to the relative safety of Maiduguri hasn’t made things easy for Muhammad’s family. They lost everything when they fled. And although tuition is free at government-run schools, Muhammad can barely cover the cost of breakfast, as it is. Add to that the expense of a uniform, school supplies and transportation, and going to school becomes all but impossible.

Tolu Olatunji, 11, does his homework in his bedroom in Abuja, Nigeria. Tolu wants to be an aeronautic engineer when he grows up.

Moving to the relative safety of Maiduguri hasn’t made things easy for Muhammad’s family. They lost everything when they fled. And although tuition is free at government-run schools, Muhammad can barely cover the cost of breakfast, as it is. Add to that the expense of a uniform, school supplies and transportation, and going to school becomes all but impossible.

But children do not all get equal opportunities to go to school, stay in school and learn what they need to know – and the disparities are not random. Data from around the world show that children’s chances of getting a quality education are lower if they come from poor families; if they live in remote rural areas; if they are girls; if they have a disability; if they belong to an ethnic or racial group that faces discrimination in their society; or if, like Muhammad, they live in an area affected by crisis. Where these factors overlap they often reinforce deprivations. For instance, the poorest rural girls in Pakistan on average benefit from half a year less education than the poorest urban girls, according to 2013 data.

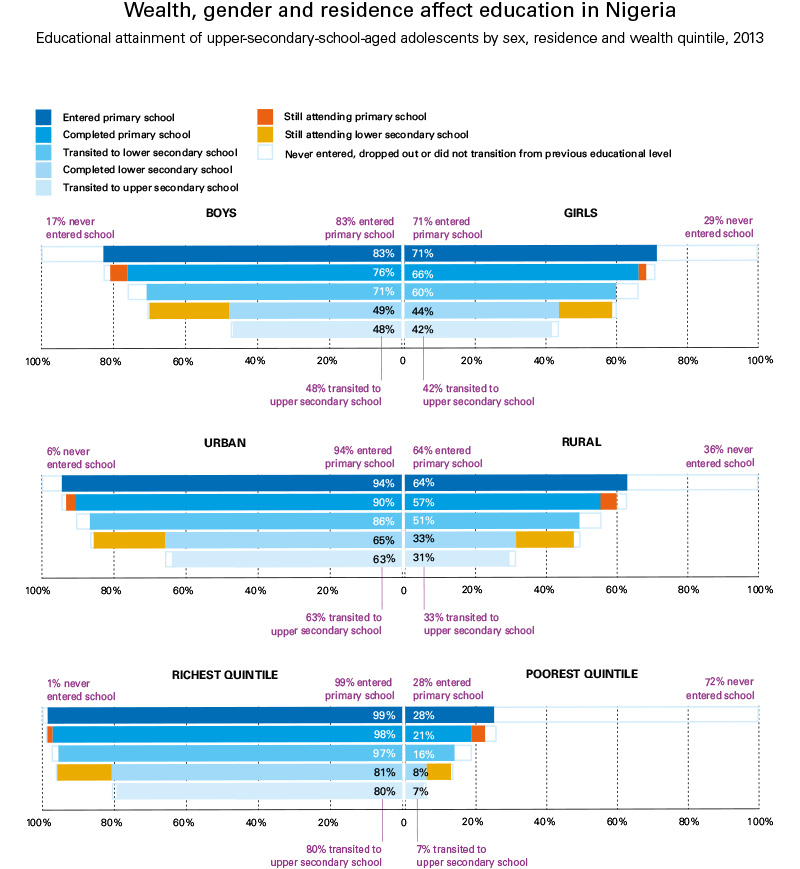

In Nigeria, disparities start early and widen as children grow older.

According to 2013 data, less than a third of poor Nigerian children between 15 and 17 years of age had entered primary school at the correct time, though nearly all of the children from richer households had. At each level of education, greater proportions of poor children drop out.

And as they drop out, their chances of rising out of poverty and overcoming disadvantage diminish. They struggle to provide for themselves, trapped in low-skilled, poorly paid, and insecure employment. They cannot help but pass on to their own children the deprivation and disadvantage that kept them from realizing their potential. The cycle of inequity grinds on.

Levelling the playing field

In the Dalori camp for internally displaced persons, on the outskirts of Maiduguri, the usual trend has been turned on its head. Home to some 20,000 people, mostly from the Local Government Area of Bama, the camp is giving many of the Area’s poorest children a chance to go to school for the first time. Before coming here, many of the children, mostly from farming communities, were accustomed to spending their days working in the fields.

Yafati Sanda is the camp’s school principal. Every morning she makes her rounds, carting a stack of blue folders from class to class to check that all is in order: that the teachers are present, that attendance has been taken, that the children’s notebooks are up to date and their backpacks are clean.

Principal Yafati Sanda reviews students’ notebooks at a UNICEF school for internally displaced children in Maiduguri, Nigeria.

She starts with Nursery 1, the pre-primary students. At least a hundred boisterous children are packed into a tent, yet somehow their teachers manage to maintain perfect command. Seated in orderly rows of five to a bench, they can hardly contain their excitement as they recite English nursery rhymes, bellowing “Rain, rain, go away!” into the dry savanna air.

Satisfied, Yafati continues on to her next stop: Primary 1A. “Good morning, Aunty”, the children greet her in unison. “How are you?” Yafati prompts them. “We are fine, thank you”, they chant back. Today, they are learning the parts of the body in English. Yafati checks the register, reminds the teacher to take the roll call and carries on to the next class.

When she arrives at Primary 2A, the room is in chaos. It is 9:30, an hour and a half after the official start of the school day, and still no teacher has arrived. Normally full of energy, Yafati is despondent. Even though there are 134 teachers for the 24 classrooms, it is a constant challenge to get them to show up to class.

“These children – since the morning they come from their home to study. Their parents, thinking that they are learning something… And you go into a class and no teacher?” She shakes her head, “I’m not happy.”

When Yafati started this school as a volunteer in May 2015, there were just 30 students. One of the initial challenges she faced was persuading parents to send their children to school.

“The parents don’t know the importance of education”, she explains. So the school launched a campaign to promote enrolment, especially among girls. “Do you need a female doctor to take care of your wife?” read posters pinned throughout the school’s walls. “Take your daughter to school.”

Today, enrolment has ballooned to approximately 8,000 students. But many of them do not actually attend.

Instead, they spend their mornings queuing for water – a line that sometimes extends a thousand people long. To help address this challenge, the school provides incentives: lunch is now delivered to the school premises and household items, like detergent, are distributed at school.

Still, the problem of teacher absenteeism has been a difficult one for Yafati to solve on her own. Apart from her regular monitoring, she has little ability to enforce attendance. The teachers, all on payroll from their Local Government Area, continue to receive their salaries whether they show up to work or not. But it’s more than a matter of dedication – many simply cannot afford the cost of transportation to the camp. Like Yafati, they live in the city, where the cost of living is exponentially higher than what they are used to back home.

With just 14 tents and 12 mobile classrooms, the school doesn’t have enough classrooms to accommodate all 8,000 students. Many school systems have dealt with this challenge through double shifts, with half the students attending morning classes and the other half attending afternoon sessions.

Educating 8,000 displaced children – paying their teachers, securing sufficient classroom space and providing the materials needed for teaching and learning – takes more than the heroic efforts of a determined and resourceful individual like Yafati. It takes money – and policies that put the needs of the most vulnerable children, whether in times of crisis or in times of normalcy, at the centre.

Yet education accounts for a small share of requests for humanitarian aid – and only a small fraction of those requests are funded. Less than 2 per cent of the funds raised by humanitarian appeals go to education. In addition to funding, educating children in emergencies requires rethinking the relationship between humanitarian and development activities. The increasingly protracted nature of today’s crises demands both rapid response and long-term solutions. Even before crisis hits, education systems need to be prepared – building the resilience of schools, teachers, students and the communities they live in, so they can respond to shocks and bounce back.

Investing in education pays dividends

In the next 15 years, the world’s population of 15- to 24-year-olds will increase by nearly 100 million. Most of these young people will be in Asia and Africa. They will be the parents who raise tomorrow’s children, the workers who keep the global economy going, the leaders who determine what kind of world we live in. Today, they are children. They urgently need the quality education to which they have a right – and the world urgently needs every one of them to get it.

On average, each additional year of education a child receives increases future earnings by about 10 per cent. Each additional year a country manages to keep its children in school can reduce that country’s poverty rate by 9 per cent. Poorer countries see the highest returns.

Learning makes a real difference, too: If all children born in lower-middle-income countries today learned basic reading and math, their countries’ GDPs could increase thirteenfold over their lifetimes. Making sure that all children can acquire these skills would also create the conditions for more equitable patterns of growth, while increasing the size of the economy and reducing poverty.

If every child has the opportunity to enter adulthood with the skills needed to build a secure livelihood and participate fully in society, the effects could transform societies and economies.

Chapter 3:

A chance to dream

World leaders have committed to ending poverty by 2030. But unless we invest in opportunities for the most vulnerable children, in 2030 167 million children will live in extreme poverty.

Shampa Akhter, 16, at her home in Khulna, Bangladesh. Shampa refused to abide by her family’s plan to marry her off at 15.

Shampa wants to be a banker when she grows up. She’s studying commerce in school, and it’s her strong suit. But she’s worried that she’ll never be able to realize her dream. Less than a year ago, her father, a day labourer and the family’s primary breadwinner, had a debilitating accident that turned her world upside down.

While the family was still reeling from the catastrophe, Shampa went to stay with her aunt, who had a solution. At 15 years old, Shampa would be married.

“Baba and Ma couldn’t afford the expense of my education”, Shampa explains between tears. “So they thought that one less family member would help – it would make things easier.”

Shampa refused to cooperate. Determined to finish her education, she enlisted the support of a local ‘adolescent club’, a group of youth activists who have been organizing for greater government accountability and an end to child marriage. All Shampa had to do was say the word, and the group sprang into action.

A posse of seven teens showed up at the doorstep of her family’s two-room bamboo hut to lecture her parents on the risks of early marriage. They explained that early pregnancy is associated with higher mortality rates for both mother and baby, that Shampa would be forced to spend her days doing household chores and that she would not be able to complete her education. They argued that if Shampa were to finish school, she would be in a better position to earn and support the family in the future. Finally – and this is what Shampa suspects did the trick – they reminded her parents that marriage before 18 is illegal in Bangladesh, and that this law is enforced.

In the end, her aunt’s scheme did not come to pass. Still, the experience rattled Shampa. “Even now”, she says, “when I recall those days, I get scared.”

Shampa’s parents have committed to supporting her through the end of the school year, so that she can attain her secondary school certificate, awarded at the end of Grade 10. But they say they cannot afford to sponsor her studies beyond that point.

Although primary school tuition is free in Bangladesh, making it through the secondary school system requires a slew of unofficial costs. Group tutoring, or ‘coaching’ before or after school, is rampant, and most students consider it essential for success. In addition to textbooks, students rely heavily on supplementary study guides, which the school does not cover. And for the very poorest, attending school comes with the opportunity cost of lost income from work.

Shampa wishes she had the choice to work instead of getting married. “If I were a boy they would not have considered marrying me off…I could have started doing some job and supported my family.” But there aren’t many options for girls: “They can only work as a maid in the house.”

Beyond the expenses associated with secondary school, for many children in remote rural areas, distance from school is an obstacle to attendance. With fewer secondary schools than primary schools, adolescents often have to travel outside their villages and communities to get to school. Some parents prefer not to risk sending their daughters to school, as they worry about harassment during the commute.

Poverty is about more than money

In 2012, almost 900 million people struggled to survive on less than US$1.90 a day – the international extreme poverty line – and more than 3 billion remained vulnerable to poverty, subsisting on less than US$5 a day. Like Shampa, they live on the precipice, just one illness, drought or other misfortune away from descending into extreme poverty.

For children and adolescents, poverty is about more than money. They experience it in the form of deprivations that affect multiple aspects of their lives – including their chances of attending school, being well nourished and having access to health care, safe drinking water and sanitation.

Arieful Islam, 13, at work in a brick factory in Satkhira, Bangladesh.

Taken together, these deprivations effectively cut childhood short, robbing millions of children of the very things that define what it is to be a child: play, laughter, growth and learning. These basic opportunities are the foundation upon which children can build their futures – and for those who have a chance to enjoy them, the world can seem full of possibilities. But for a child like Arieful Islam, who is out of school because he needs to work just to pay for his daily meal, even dreaming is beyond reach.

Arieful has never had the chance to consider what he wants to be when he grows up. At just 12 years old, Arieful has been working for longer than he can remember. He started in the fisheries when he was in the first grade, and then later began an ‘apprenticeship’ in the brickworks – unpaid labour that typically comes with a meal. Today, he is a regular labourer at a brick factory where he works alongside much of his family. During the off-season, his mother borrows money from the factory owner just to make it through the rest of the year. The entire family works to pay back the loan the following season.

Arieful, who missed the opportunity to go to school as a young boy, is now enrolled in a second chance education programme that runs in the evening. The programme provides a small stipend, but it’s not enough to compensate for the US$3 a day he earns as a brick worker. During brick season, when work is busy, his attendance is irregular.

Arefin Hasan, 12, practises fractions during a math lesson at his public/private school in Khulna, Bangladesh. Inspired by the pioneering thinkers he has read about in his textbooks, Arefin wants to be a scientist when he grows up. “I want to invent something so that people remember me after I die.”

Because children experience poverty in multiple ways, simply providing services – such as health care and education – is not enough to provide each a fair chance. Even if education is free, a child like Shampa may not be able to afford the costs of getting to school or buying supplies – or, like Arieful, may not be able to afford to miss out on a day’s work. The most disadvantaged children need the means to access these services.

Social protection programmes like cash transfers are one way to reduce families’ vulnerability to poverty and deprivation and surmount some of the barriers that can keep children from taking advantage of the services available to them. Cash transfers provide a minimum level of income that can help keep the poorest, most vulnerable households out of destitution. They can also provide a ladder out of poverty and open up access to services – like education – that are critical to building children’s futures. By one estimate, social protection initiatives keep some 150 million people out of poverty. Cash transfers can also address some of the factors that keep children from entering school or force them to drop out.

Breaking the vicious cycle

Fourteen-year-old Jhuma Akhter is back in school and performing at the top of her class thanks to a cash transfer programme. Getting here hasn’t been easy.

When Jhuma was just 8 years old, she left school to work as a servant in an abusive home. She spent three years there, and was never paid for her labour or allowed to attend school. She worked in exchange for her upkeep and the promise that,

Jhuma Akhter, 14, does her homework beneath a lamppost outside her home in Khulna, Bangladesh.

Eventually, Jhuma’s mother allowed her to return home. But every day after school, Jhuma would head to work, going door to door to beg for rice. One day, as they sat eating their rice on the stoop of their tin-roofed shack, Jhuma explained to her mother that as she advanced from one grade to the next, the costs of school would increase. She would need tutoring, study guides and notebooks not provided by the school. So her mother decided it was no longer worthwhile to send her to school – and instead brought her along to work. Working full time supplying water to local businesses, Jhuma brought in approximately US$7 a month.

That’s when Nazma, a community volunteer, spotted Jhuma. “They were looking for kids like us”, Jhuma explains. Nazma invited Jhuma and her mother to a few meetings to assess the family’s needs and eventually enrolled them in a cash transfer programme conditional upon Jhuma’s attendance at school. Now that her mother receives two annual instalments of approximately US$150, Jhuma has returned to school. She is in Grade 7.

In the neighbourhood, Jhuma is no longer known as the girl who carries water. Instead, she is recognized by her new routine. Every evening after prayers, she hauls a plastic folding table and chair out by the garbage dump at the bend in the road so she can do her homework under the glow of the lamppost. Ever resourceful, she writes her assignments on the back of political campaign posters left over from the most recent election.

Today, when Jhuma imagines the future, marriage is no longer part of the picture. In fact, she thinks girls should wait till they’re at least 22, well beyond the 18 years minimum dictated by the law. Instead, Jhuma now dreams of one day becoming a doctor. “I want to provide care for everybody.”

Chapter 4:

A call to action

“Inequality is a choice. Promoting equity – a fair chance for every child, for all children – is also a choice. A choice we can make, and must make. For their future, and the future of our world.”

– Anthony Lake, UNICEF Executive Director

Susmita Mondal, 18, is an activist against child marriage in her community, Dacope, Bangladesh.

The life prospects of children trapped in intergenerational cycles of poverty and disadvantage might seem like a matter of chance – an unlucky draw in a lottery that determines which children will live or die, which have enough to eat, can go to school, see a doctor or play in a safe place.

But while children’s origins are largely a matter of fate, the opportunities available to them are not. They are the result of choices – choices made in our communities, societies, international institutions and, most of all, our governments.

We know that the right choices can change the lives of millions of children – because we have seen it. National action, new partnerships and global commitments have helped drive tremendous – even transformational – change. Children born today are significantly less likely to live in poverty than those who were born 15 years ago. They are over 40 per cent more likely to survive to their fifth birthday and more likely to be in school.

But far too many children have not shared in this progress.

Reaching these forgotten children must be at the centre of our efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, which pledge to leave no one behind. The 2030 goals cannot be reached if we do not accelerate the pace of our progress in reaching the world’s most disadvantaged, vulnerable and excluded children.

Unless we act now, by 2030:

Over 165 million children will live on no more than US$1.90 a day – 9 out of 10 will live in sub-Saharan Africa.

Almost 70 million children under the age of 5 will die of largely preventable causes – and children in sub-Saharan Africa will be 10 times as likely to die as those from high-income countries.

More than 60 million children aged 6 to 11 will be out of school – roughly the same number as today.

750 million women will have been married as children.

We must reverse this course – and we can. Inequity is not inevitable; nor is it insurmountable. With the right investments, at the right time, we can reduce the inequities that limit children’s life chances today, so that they can lead more productive lives as adults and pass on more opportunity to their own children. We can transform the vicious cycle of disadvantage into a virtuous cycle of equity that benefits all of us.

The State of the World’s Children 2016 report is UNICEF’s call to action, urging governments and development partners to translate 2030 commitments into concrete action to reach the most disadvantaged children.

Drawing from the work of UNICEF and partners, the five key areas that follow – information, integration, innovation, investment and involvement – represent broad, often overlapping, pathways to equity. They encompass operating principles and critical shifts that can help governments, development partners, civil society and communities shape policies and programmes with the potential to make that fair chance a reality for every child.

Pathways to equity

Information

Information – broadly encompassing data about who is being left behind and how programmes are reaching or failing to reach those in greatest need – is a first operating principle of equitable development. Data broken down by the factors that contribute to disadvantage – including wealth, gender, ethnicity, language and location – help identify the most disadvantaged children. Equipped with such data, governments and development partners can target programmes to expand opportunity – for instance, through cash transfers to help families pay school fees.

By establishing national equity targets – and milestones towards achieving them – governments can drive progress towards the 2030 goals and improve the lives of their youngest and most disadvantaged citizens.

Integration

Integration in how we approach programming, policy and financing can better address the overlapping dimensions of deprivation, which affect children’s health, education and so many other aspects of their lives. Integrating interventions across these separate sectors is more effective than addressing them individually. For example, the introduction of school feeding programmes has been linked to increased learning and cognitive development in Bangladesh.

And as conflicts grow more protracted and crises more numerous, bridging humanitarian and development efforts can help countries to be better prepared to meet the needs of the most vulnerable children when crises strike – while using emergency response to lay a foundation for stronger, more resilient communities and systems.

Investment

Investment that targets the most disadvantaged children can give them the opportunity to compete on a level playing field with those from more privileged backgrounds. Budgeting decisions should pay close attention to the impact on the poorest, most disadvantaged children and families. Public-private partnerships can also create innovative mechanisms for financing development and delivering critical supplies such as vaccines, insecticide-treated mosquito nets and nutritional supplements to the most excluded children and communities. Among the most successful examples of such an innovative partnership is GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, which helps shape markets and make vaccines more affordable for developing countries.

Innovation

Innovation in development can help deliver essential goods, services and opportunities to the hardest-to-reach children and communities more efficiently and cost-effectively. Innovations range from ingenious applications of promising new technologies, like drones delivering blood samples for early infant HIV diagnosis, to creative local solutions like floating schools in flood-prone areas, to new kinds of financing partnerships.

Involvement

Involvement is critical to sustainable development. Durable change won’t come from the top down – its fuel comes from social movements and engaged communities, including children and young people themselves. Governments, international organizations and civil society, working closely with communities, can better address common challenges, such as coping with the effects of climate change, lifting children out of extreme poverty, promoting the rights of girls and women and, fundamentally, expanding opportunity for all, so that children born into poverty, conflict and disadvantage can realize their right to a fair chance in life.

With concerted action, guided by these five principles, we can drastically reduce inequalities in opportunity for children within a generation. It’s the right thing to do, and the smart thing to do. Now is the time to chart our course towards a more equitable world.